Posts Tagged ‘experimental’

[music:] Gustoforte, Gustoforte (1985)

A sonic guerrilla squad featuring videomaker Roberto Giannotti (vocals, drums, keyboards, tapes), Stefano Galderisi (basses, keyboards, tapes – formerly of surf-rockers The Sentinels), Il Maestro (“the master”, later identified as the singer-songwriter Francesco Verdinelli, on guitars, keyboards and tapes) and La Donna (“the woman”, possibly actress and scriptwriter Roberta Lerici, on vocals, drum machine, percussions, tapes) started the band called Gustoforte (“strong taste”) in Rome in 1984.

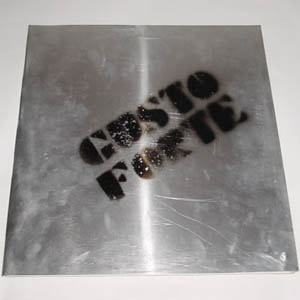

This self-titled album released by Rat Race label early in 1985 with liner notes by Ado Scaini of The Great Complotto fame, which in the first 200-copies run came in a real steel cover, remains unfortunately the only evidence they left behind – a stunning, savage post-everything epic which each time brings to mind Virgin Prunes at their most demented and free-form, This Heat, The Residents, or even Claudio Rocchi’s attempts in electronics, and clangs in unison with the noises of contemporary experimental rock outfits such as, just to name one, Black Dice, or catastrophic dub suppliers of Excepter’s caliber.

The record follows the storyline suggested by an anti-utopian sci-fi plot, just like in an old-fashioned concept album: a travelling salesman visits a factory just to discover that there’s only one human worker left, contently attending 24/7 a useless assembly line, with all the time in the world to think. A robot escorting the representative in a tour of the plant explains him that unreliable workers have been completely replaced with machines. The only other humans around are dismissed trade unionists, just sitting around in a room, drinking and recalling the old days. The rep is then introduced to the factory coordinator: a powerful female supercomputer who manages to seduce him and eventually turn him into a bionic salesman working for the company.

Here is the tracklist:

01, s. Antony Chain

02, Steel Walk

03, Ventiquattro tre 84 (“twenty-four three 84”)

04, Assembly Line

05, Evry Courcouronnes

06, Factory ab absurdo

07, Ask Me Dream

08, Bionic Promotion Agent

Get it: Gustoforte, Gustoforte (1985)

Gustoforte reportedly recorded an unreleased second album, called Souvenir of Rome, before Giannotti and Verdinelli quit the band in 1994. Drummer Franco Calbi, performer Domenico Vitucci and Texan avant multi-instrumentalist and self-made instruments wizard Chris Blazen were recruited by the end of Nineties by Galderisi to keep the project alive. Anyway, the current line-up credited in their basic MySpace page features only the four original members.

[music:] Enzo Delre, Il banditore (1974)

A revolutionary avant-folk storyteller, an arte povera experimental performer, an “oggettista corpofonista” (“objectist bodyphonist”) as he defines himself, Enzo Del Re or Delre – as spelled on this album’s cover – born in 1944 in Mola di Bari, Apulia, South-East of Italy, has been one of the few italian artists, together with Francesco Currà, to apply to music, maybe unknowingly, the well-known Jean-Luc Godard’s plea: “it’s not about making political films, but rather making films politically” (I’m quoting by heart).

A restive anarchist, soon after graduating at the local conservatory he abandoned the academy to pursue a personal and unique musical language caught between roots and modernity, coherence and contradiction, folk singleness and cultured experimentalism, joined in his research by the ethnomusicologist Antonio Infantino; as a proletarian musician who merely had at his disposal his own sheer working force, his hands, his arms, his legs, Del Re chose to play only significant found objects and recycled materials, used as percussion instruments – mostly chairs, as a nonverbal and sorrowful protest against electrocution and death penalty in general, or a suitcase, as in Vittorio Franceschi’s Qui tutto bene… e così spero di te (“things are fine here… and so i hope with you”, 1971), a theatrical play about “emigration and imperialism” – and clicking his tongue and beating his own body and face. A radical, marginal sound worker, who in the Seventies used to take three shifts a day, playing two gigs for free at occupied factories, schools, universities, and getting for the last one a metal worker’s daily minimum wage. The same continuous and monotonous rythm he used as sole accompaniment to his songs seemed produced by a clapped out assembly line.

Il banditore (“the town crier”) – released in 1974 after his experiences with Dario Fo’s theatrical company Nuova scena (“new stage”) and at the legendary Derby Club in Milan with Enzo Jannacci, and following his 1973 debut album Maul (“Mola” in local dialect) – is a full and detailed report about the work of this postindustrial agit-prop cantastorie who tirelessly travelled all over the country, spreading his word and critically supporting the revolutionary movement.

The record testified his immutable and hieratic style, seemingly coming from an ancient past or from a far future, inducing a sort of ecstatic experience by iterativity; an uninterrupted stream which made live together tarantella with musique concrète, The Last Poets with his hometown fishermen’s screaming (even if Enzo’s voice tone and the way he offers lyrics remind insistently of Luigi Tenco). However, there are moments which stand out of the flow, as the title track with its comics’ onomatopoeias and the siren in the end, between an anti-aircraft alarm and a factory hooter; the ritual latin mixed with real and fake advertising claims of “Laudet et benedicitet (Infantino)”; the ironic thirdworldist namedropping of “Comico”: hints of a sadly unaccomplished mediterranean cannibalism – in the sense of the Manifesto Antropófago by Oswald de Andrade, which inspired the Tropicália movement. And, of course, the dazzling dyptich of “Lavorare con lentezza” and “Tengo ‘na voglia e fa niente”, written in an hotel room in Bologna, which represents one of the most revolutionary anti-work statements ever.

Here is the tracklist:

01, Il banditore (“the town crier”)

02, Lavorare con lentezza (“working slowly”)

03, Tengo ‘na voglia e fa niente (“i feel like doin’ nuthin'”)

04, Laudet et benedicitet (Infantino)

05, La fretta (“the hurry”)

06, La sopravvivenza (“the survival”)

07, Il superuomo (“the superman”)

08, Voglio fare il boia (“i wanna be a hangman”)

09, Scimpanzè (“chimpanzee”)

10, La 124 (“the 124”, referring to a FIAT car model)

11, Comico (“funny”)

12, La rivoluzione (“the revolution”)

Get it: Enzo Delre, Il banditore (1974)

Unbeknown to him, “Lavorare con lentezza” was used as broadcasts’ opening and closing signature tune by Radio Alice, the movement’s pirate radio in Bologna, from 1976 until March 12th, 1977, the day after the killing of the student Francesco Lorusso by a carabiniere during a streetfight, when the police burst in the studios and terminated transmissions.

In 2004, Guido Chiesa directed a movie about the story of Radio Alice, titled Lavorare con lentezza and featuring the song in its soundtrack. This led to a short-lived rediscovery of Del Re’s work, which anyway didn’t particularly affect his semi-retirement, as for the tribute that fellow musicians such as Eugenio Bennato, Daniele Sepe, and Etnoritmo paid him covering or sampling his songs.

He still plays concerts occasionally, where his self-produced tapes or cd-r’s are available to buy. You can happen to meet him around his hometown’s port, where he usually sits with old fishermen speaking, drinking, and playing cards.

[music:] Mauro Pelosi, Mauro Pelosi (1977)

In 1977, the students and workers’ movement in Italy reached a peak of violence and defy. People from Autonomia Operaia, one of the most important leftist groups, used to parade with real guns in their hands; policemen not only had guns as well, but were eager to use them. As a result, many demonstrations ended up in gunfights, sometimes with dead people.

At the same time, a new and creative counterculture was rising, oddly influenced by punk, Living Theatre, french situationism, Woodstock peace-and-love philosophy, and boosted by drugs such as heroin, plegin (amphetamine-based diet pills), weed, and sedatives. Both the “regular” revolutionaries and the establishment looked suspiciously at those people, like the Indiani metropolitani (“urban red-indians”), and at what they did.

In the middle of all this, Mauro Pelosi released his third album. A masterpiece.

His first two records, La stagione per morire (“a season to die”, 1972) and Al mercato degli uomini piccoli (“at little men’s market”, 1973), released on Polydor major label, were pretty undecided between a “cantautore” style (“cantautori” were the singer/songwriters , tipically engaged and/or depressed, which many young people adored), and prog-like tentatives. Most of the lyrics were self-centered, dealing with love disappointment and suffering, and deeply introspective. Actually, there are great songs in these albums, and even some “experimental” takes which anticipate what was yet to come (like “Suicidio” on La stagione per morire), but the overall impression is that Pelosi’s vision was slightly out of focus.

After the commercial failure of his early seventies’ efforts, Mauro Pelosi took his time, preparing for the next move. He was allowed another chance by Polydor, which in the meantime released a compilation album, but he apparently gave up the opportunity, travelling to Far East and making his living by selling cheap indian jewelry in the streets of Rome, his hometown. Until one day, in 1976, he came back to his label’s offices. He was ready to record again.

It seemed he had absorbed all of the anger, the love, the sadness, the frailty, the unfulfilled dreams and the self-injuring instincts of his generation, the political discontent of the extremists and the freaky attitude of the Indiani metropolitani. And he was ready to give it back in the form of nine songs.

Everything is in its place here, even the faux pas, the naiveties, the excesses. In this self-titled LP, Pelosi simply and completely wastes himself, speaking on behalf of his generation, and no more just for himself, with relentless self-irony. It’s a sacrifice. He destroys himself, and everything else.

A morbid mood haunts the whole album, a feeling like the musicians – and the singer first, of course – could suddenly lose their heads and start eating their instruments, or kill each other. The music is kinda psychedelic pop, with some progressive and experimental hints, cabaret and child music passages, and even great orchestral moments, such in the magnificent, Bacalov-esque coda for “Ho fatto la cacca”, the final track. The backing band counts musicians such as the great Lucio Fabbri (Premiata Forneria Marconi, Demetrio Stratos, Claudio Rocchi, Eugenio Finardi…), Ricky Belloni (formerly with New Trolls), Bambi Fossati (Garybaldi), and Edoardo Bennato.

Useless to say, Mauro Pelosi sold little more than the previous two albums, and after another beautiful LP in 1979, Il signore dei gatti (“the cats’ master”), Pelosi was discharged by his label and completely disappeared from the italian music scene.

Here is the tracklist:

01, La bottiglia (“the bottle”)

02, Luna park

03, Ho trovato un posto per te (“i found a place for you”)

04, Una lecca lecca d’oro (“a golden lollipop”, also released as a 7″ b/w “L’investimento”)

05, L’investimento (“the investment”)

06, Una casa piena di stracci (“a house full of rags”)

07, Alle 4 di mattina (“at four in the morning”)

08, Claudio e Francesco (“Claudio and Francesco”)

09, Ho fatto la cacca (“i poo poo’ed”)

Get it: Mauro Pelosi, Mauro Pelosi (1977)

For those of you who can read italian, here is the artist’s self-managed site: mauropelosi.it